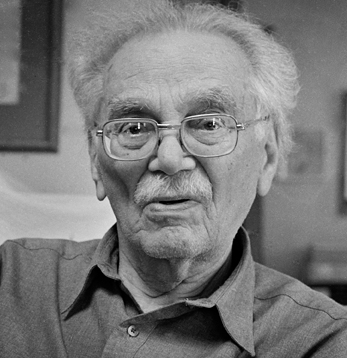

Milton Rogovin died this month at the age of 101. Although I only met him once, through his photographs and writing he has been one of my mentors.

1998 photo by Howard Zehr

As NPR noted in his obituary, Rogovin’s life was about seeing, though the methods changed. He began his professional life helping others to see, as an optometrist in Buffalo, New York. Because of his activist involvements for the poor, he was more or less forced out of his occupation by the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s. As his patient base shrank, he began making photographs in the hopes of helping us to see the injustices around us and the people impacted by them.

Rogovin’s photographs were always about people, always about the rural and urban underclass. One of his most important projects was close to home, in the economically depressed areas of Buffalo, though he also photographed in Chile, Yemeni and other countries. “All my life, I’ve focused on the poor,” he said in a Washington Post quote. “The rich ones have their own photographers.” He allowed people to pose themselves, always portraying them with dignity and individuality, not as victims. His subjects were photographed straightforwardly, in their own environments.

Two of his books have had an especially significant influence on me. The Forgotten Ones contains a variety of series of working people from around the world. My favorite, though, is “Working People, 1977-80.” This photo essay is made of a series of diptychs. On one page is a portrait of individual workers in heavy industry, often mining, posed in their work environments. On the facing page is a portrait of the same person at home. The contrast is often dramatic; sometimes it takes a second look to realize they are the same people. The pairing of these photos creates a much richer portrait than a single image.

Rogovin took the concept of paired images further in his book Triptychs: Buffalo’s Lower West Side Revisited, expanding each grouping to three images made over several decades plus years. After initially doing portraits in the 1970s, he returned to the community in the 1980s and again in the 1990’s, locating the same people and re-photographing them. It is fascinating to see how people change, and don’t change, over the years. This inspired my own small series of portraits over time, some of which can be seen on my photo website www.howardzehr.com.

In my interview with him, Rogovin said something that I identified with: “Going from one series to another is a very difficult thing for me, and especially my wife. I get kind of grumpy and worried that I’ll find another series that’s important.” I too feel at lose ends when I don’t have a focus for my photography.

After finding that fancy equipment generated too much attention in his working environments, Rogovin adopted a simple, non-intrusive approach: a Rolliflex medium format camera, often on a tripod, and a bare-bulb flash.

Do photographs change the world? In The Forgotten Ones Rogovin says, “…I used to think that photography would do everything, but now I don’t think so. It takes photography, it takes sociology, it takes working people, it takes teachers – and a lot of different people to help make the change. See, it isn’t just the photographs.”

He cites the early documentary photographer Jacob Riis: “Jacob Riis, when he was very despondent at the results he was getting, said he would go to a friend of his who was a stonecutter and he would watch him work. The stonecutter would hammer that stone once, twice, ten times and nothing happened. Fifty, a hundred times and nothing happened. Then, after the hundred and first blow, the stone would split, and Riis said it was obvious that it wasn’t’ the last blow that did it. It was all the blows together. That’s my feeling. It wasn’t the photographer – his or her photographs – that’s going to do it, but all the hundred and one different blows added together to make a change.”

This image has inspired my work in justice as well as photography.